Japan: PhotoVoice Project

in the Aftermath of the 2011 Great East Japan Disaster

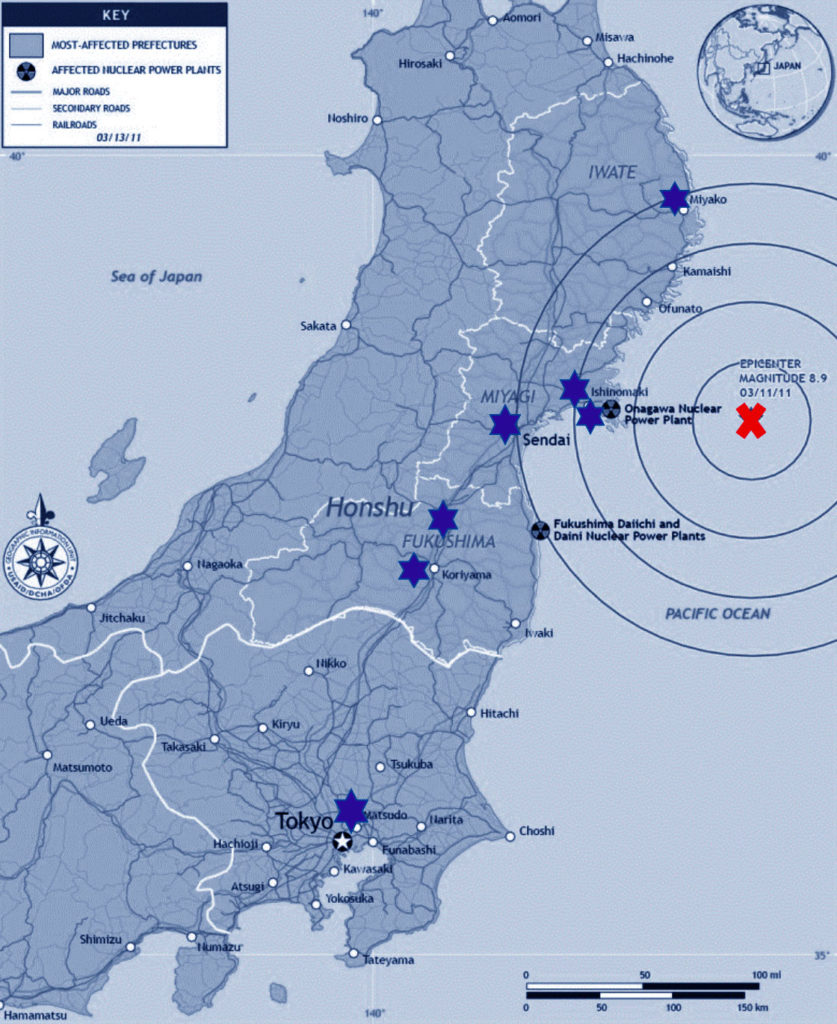

Current Project Locations: Miyako City, Iwate Prefecture; Sendai City, Ishinomaki City, and Onagawa Town, Miyagi Prefecture; Koriyama City and Fukushima City, Fukushima Prefecture; Tokyo Metropolitan District

Map of Japan adapted from catch4all.com

PI: Mieko Yoshihama, Ph.D., Professor, School of Social Work

Japanese Team

Co-PI: Tomoko Yunomae

Staff: Ayako Ohno; Atsuko Matsusato; Shigeyo Nagashima; Kazumi Shiraishi and many volunteers and supporters

From Gender Gap to Gender Justice: Making Women’s Voices Heard through PhotoVoice

In 2011, the year of the Great East Japan Disaster, Japan ranked 98th out of 135 countries on the Gender Gap Index (121st out of 153 countries in 2019). Given women’s lower status in society, it is no surprise that their perspectives are not well reflected in disaster policies and programs in Japan.

Using PhotoVoice methodology, the project seeks to document and analyze the disaster’s impact from the perspectives’ of women affected by the calamity and formulate recommendations for making disaster policies and programs more responsive to diverse and marginalized populations. As a participatory action research effort, the project is also intended to strengthen participants’ capacity to take action, and incite action on the part of others, to strengthen disaster policies and programs (see Yoshihama, 2018, 2019; Yoshihama & Yunomae, 2018).

In collaboration with local women’s NGOs, the project began in June 2011 in the three most severely affected prefectures—Koriyama City, Fukushima Prefecture; Sendai City, Miyagi Prefecture; and Miyako City, Iwate Prefecture. The project has since expanded and is currently operating in seven sites with over 55 members <Link Current Project Locations>.

On an ongoing basis, members take photographs of their lives and communities and discuss their experiences and observations in a small group. Ongoing collective, critical analyses lead to uncovering political and socio-cultural factors at play, exposing failures of disaster policies and programs and implicating the capitalism and neoliberalism. Through these dialectic processes, we explore and formulate visions for change. At various points, members create “voices,” written messages to convey their critical reflections, analyses, and recommendations. A recent award from the Japan Society of Social Design Studies affirms the contribution of the PhotoVoice Project to a new model of social design/planning.

Photographs and voices are disseminated in print, digitally, or through exhibitions and public forums/presentations to promote public awareness and improve social policies and programs. In addition to an interactive workshop and exhibitions at the United Nations World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in 2015, about 60 exhibitions and 30 community forums/presentations have been organized across Japan and abroad. Two books of members’ photographs and voices have been published (PhotoVoice Project, 2015, 2018). At the request of the National Women’s Education Center, selected photographs and voices have been uploaded to the center’s national archive , which is linked to the Great East Japan Earthquake Archive of the National Diet Library of Japan (the equivalent of the U.S. Library of Congress).

Members, women affected by the disaster, are actively engaged not only in the creation of empirical knowledge through photo-taking, group discussions, and voice writing, but also in the dissemination of such knowledge to inform policymakers, practitioners, the media, and other citizens, prompting them to take action in their respective capacities. Clearly, PhotoVoice promotes cyclic processes of critical consciousness and action—praxis.

This project is breaking the monopoly of knowledge creation by so-called “experts,” and inserting women’s perspectives into public discourse on more inclusive policies and responses.

The Great East Japan Disaster and Women, March 11, 2011

At 14:46 Japan Standard Time on March 11, 2011, a 9.0-magnitude earthquake struck the northeast region of Japan, which triggered massive tsunamis. This earthquake represented the largest earthquake in the recorded history of Japan (Japan Meteorological Agency, 2012).

The combination of the earthquake and tsunami caused devastating damage to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, located approximately 180 km southwest of the epicenter of the main shock. A series of three explosions occurred on March 12, 13, and 14, respectively, and released a high dose of radioactive material, whose effects continue to this day. The accident was rated 7—the highest level on the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES).

This cascade of disasters caused (and continues to cause) destruction to human lives and the natural and built environment, claiming over 19,500 lives; over 2,500 people remain missing (Fire and Disaster Management Agency, 2019; National Police Agency 2019; Reconstruction Agency 2019).

Gender & Disaster

Decades of research and field work around the world have shown that disasters exacerbate pre-disaster inequities and magnify the vulnerability of marginalized groups (Enarson, 2012; Wisner et al., 2003). Unquestionably, women in Japan have been marginalized, as the Gender Gap Index (World Economic Forum) shows year after year: 98th out of 135 countries in 2011; 121st out of 153 countries in 2019.

Prior to the 2011 Great East Japan Disaster, disaster policies and programs in Japan has paid little attention to gender. Likewise, research on disaster in Japan has paid limited attention to gender, and no study has used participatory methods of investigation to capture women’s lived experiences and perspectives. The PhotoVoice Project is aimed at filling these serious gaps in social policies, programs, and research.

The Same as Five Years Ago

The Same as Five Years Ago“There’s no place to dispose of these bags; when they’re taken away, they’re replaced with more bags. There are a lot of places like this.

We live so close to this hazardous material, and now no one even bothers to measure the radiation. I fear that we’re becoming numb to the situation.I just want my life back — a life where we can feel safe.”Ki-chan

Photo: Kawauchi Village, Fukushima Prefecture, July 2016

PhotoVoice

PhotoVoice is a participatory approach to identify and analyze community issues and formulate plans for change. It was originally developed during the 1990s by U.S.-based researchers as a participatory tool for community assessment and policy advocacy (Wang 1999; Wang & Burris 1994, 1997).

Rooted in empowerment and emancipatory education (cf., Freire, 1970), feminist theory, and documentary photography, PhotoVoice engages the very people affected by the social issue under investigation. Participants serve as experts, producing knowledge through photo-taking and dialectic discussions. Along the way, they create voices (i.e., short written texts) to accompany selected photographs.

As a participatory action research methodology, PhotoVoice recognizes women (and other marginalized groups) as authorities and legitimate creators of knowledge (Maguire 1987; Yoshihama & Carr, 2002). Through critical reflection and dialogue, participants in PhotoVoice projects engage in knowledge production in a reflexive, inclusive, and collaborative manner. Such collectively produced knowledge motivates members to take action to improve the conditions in which they live (Beh et al., 2013; Bell 2015; Yoshihama, 2018, 2019; Yoshihama & Yunomae, 2018).

Selected References

Beh, A., Bruyere, B. L., & Lolosoli, S. (2013). Legitimizing local perspectives in conservation through community-based research: A Photovoice study in Samburu, Kenya. Society and Natural Resources, 26, 1390-1406.

Bell, S. E. (2015). Bridging activism and the academy: Exposing environmental injustices through the feminist ethnographic method of Photovoice. Human Ecology Review, 21, 27-58, 199.

Enarson, E. (2012). Women confronting natural disaster: From vulnerability to resilience. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Fire and Disaster Management Agency. (2019, January). Appendix I. Number of deaths by prefecture and damage to residential buildings caused by the Great East Japan Disaster as of September 1, 2018. In 2018 White Paper on Fire Service [in Japanese]. Tokyo, Japan. Retrieved from www.fdma.go.jp/publication/hakusho/h30/data/38011.html

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

Japan Meteorological Agency. (2012, December). Report on the 2011 Off the Pacific Coast of Tohoku Earthquake (Technical Report No. 133) [in Japanese]. Retrieved from www.jma.go.jp/jma/kishou/books/gizyutu/133/ALL.pdf

Maguire, P. (1987). Doing participatory research: A feminist approach. Amherst, MA: Center for International Education, School of Education, University of Massachusetts.

National Police Agency (2019, September 10). 2011 police responses and damage caused by the 2011 Off the Pacific Coast of Tohoku Earthquake [in Japanese]. Retrieved from www.npa.go.jp/news/other/earthquake2011/pdf/higaijokyo.pdf

PhotoVoice Project (Ed.). (2015, March 16). Our PhotoVoice of 3.11, 2011: Then, now, and moving forward (PhotoVoice Book No. 1) [in Japanese]. Tokyo, Japan.

PhotoVoice Project. (Ed.). (2018, February 10). Visions for more effective disaster prevention and reconstruction: PhotoVoice from women affected by the Great East Japan Disaster (PhotoVoice Book No. 2) [in Japanese]. Tokyo, Japan.

Reconstruction Agency. (2019, June 28). The number of disaster-related deaths attributable to the Great East Japan Disaster as of March 31, 2019 [in Japanese]. Retrieved from www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat2/sub-cat2-6/20190628_kanrenshi.pdf

Wang, C. C. (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health, 8, 185-192.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1994). Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Education & Behavior, 21, 171-186.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24, 369-387.

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2003). At risk: Natural hazards, people’s vulnerability, and disasters (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Yoshihama, M. (2018, May). PhotoVoice: Arts-based participatory research and action in post-disaster Japan, Social Dialogue. 19, 28-30.

Yoshihama, M. (2019). PhotoVoice Project: A participatory research and action in post-disaster Japan. In E. Huss & E. Bos (Eds.), Art in social work practice: Theory and practice – international perspectives (Chap. 5, pp. 57-67). London & New York: Routledge.

Yoshihama, M., & Carr, E.S. (2002). Community participation reconsidered: Feminist participatory action research with Hmong women. Journal of Community Practice, 10(4), 85-103.

Yoshihama, M., & Yunomae, T. (2018). Participatory investigation of the Great East Japan Disaster: PhotoVoice from women affected by the calamity. Social Work. 63(3), 234–243.

Partner Organizations

- Ajisai no Kai (Miyako City, Iwate Prefecture)

- Ekubo House (Onagawa City, Miyagi Prefecture)

- Hearty Sendai NPO (Sendai City, Miyagi Prefecture)

- peach heart (Koriyama City, Fukushima Prefecture)

- Women’s Space Fukushima NPO (Koriyama City, Fukushima Prefecture)

Sponsors

The PhotoVoice Project has been supported by grants and in both Japan and the USA.

The USA:

- University of Michigan: School of Social Work; Center for Japanese Studies; Institute for Research on Women and Gender; Center for Global Health

- Americares, Connecticut

- Japan Foundation Research Fellowship in Japanese Studies, New York

Japan:

- The Bodyshop Japan Nippon Foundation

- Camera & Imaging Products Association (CIPA) Photo Aid Program

- Fujieda Fund for Gender Equality in Responding to the Great East Japan Disasters

- Japan Post Group, New Year’s Postcard Donations Aid Program

- Kazuko Takemura Feminist Fund

- Olympus Corporation

- Oracle Charitable Trust

- Oxfam Japan

- Religions for Peace WCRP Japan, Fukushima Community Building Support Project

- Takeda Life Reconstruction Program

- The Univers Foundation Wesley Foundation Japan

- Yahoo! Foundation

Translation Support

Translation of project materials are made possible by the contribution of the faculty and students at:

- University of Michigan Japanese Language Program;

- Paris Diderot University (Université Paris Diderot) Department of Language and Civilizations of East Asia